The early history of anime stretches from silent shorts in the 1910s to television milestones in the 1960s. This countdown starts with formative TV hits that shaped the medium and builds back to the earliest known Japanese animation ever found. Each entry highlights why it matters and what makes it a lasting reference point in animation history.

Dates and credits are based on widely documented releases and archival findings. The order counts down to the oldest surviving work, with attention to firsts such as the first color feature, the first TV series and the first feature-length anime. Where prints were lost and later rediscovered, that context is noted to keep the record clear.

#12 Astro Boy (1963)

Astro Boy was the first half-hour TV anime series to air weekly in Japan. Created by Osamu Tezuka and produced by Mushi Production, it set the template for TV production schedules and the limited-animation techniques that let studios deliver episodes at scale. Its success made television the center of anime distribution for decades.

The show’s look and tone helped define the “anime style” for viewers around the world. Its mix of action and moral themes made a small team’s work feel ambitious, proving that a regular TV slot could carry character-driven stories with big ideas. That model influenced studios that followed, from storyboarding to merchandising.

Tezuka’s approach also pushed a shift in labor and budgeting. By embracing stylization and strong layouts, the series found a balance between cost and impact that many productions still reference. The result was a new path for long-running shows and a broader audience for anime on TV.

#11 Otogi Manga Calendar (1961)

Otogi Manga Calendar is widely cited as the first anime television series. Episodes were brief and educational, presenting bite-size historical anecdotes with gags and fast cuts. That format demonstrated how animation could fill regular TV slots before the era of longer weekly serials.

The series showed broadcasters there was demand for animated programming beyond theatrical shorts. It also normalized production pipelines for frequent TV delivery, paving the way for studios to organize staff, assets and reuse strategies at scale. Its impact is felt in everything from short-form educational clips to daily animated segments.

While the style was simple, the show proved television was a reliable home for animation. That proof of concept came just in time for the early 1960s boom that produced Astro Boy and other foundational TV titles, shaping expectations for pacing, music cues and episodic structure.

It also preserved a tone of curiosity and humor that many later kids’ shows borrowed, mixing facts with light comedy to keep young viewers engaged.

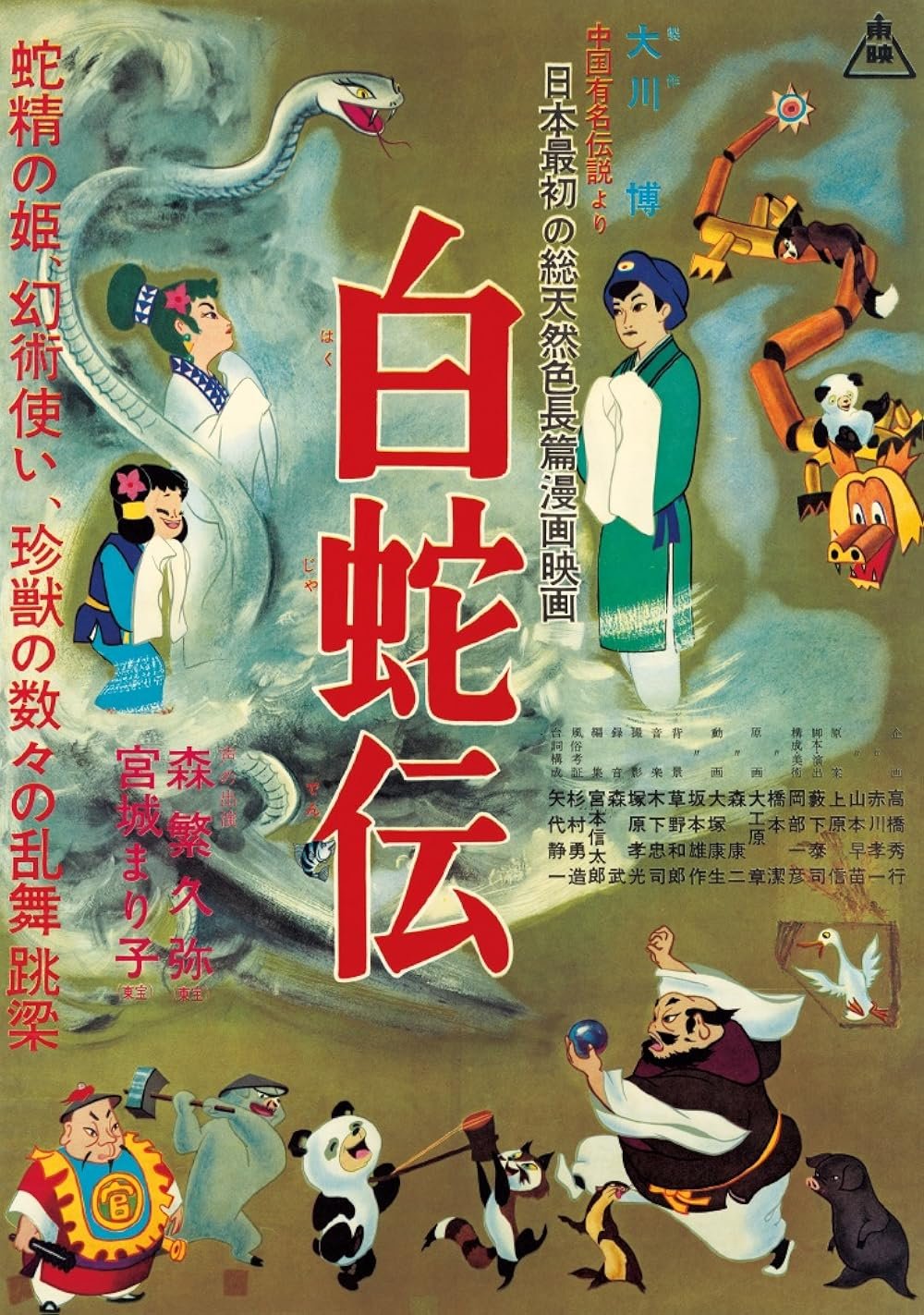

#10 The Tale of the White Serpent (1958)

Toei’s The Tale of the White Serpent (Hakujaden) is recognized as Japan’s first color feature-length animated film. It set Toei Doga’s ambition to be the “Disney of the East,” with lush backgrounds, musical set pieces and full-animation passages uncommon in Japanese productions at the time.

The movie also helped train a generation of artists who would lead the industry in later decades. Its workflows, from clean-up to inking and painting, established Toei’s studio playbook and professionalized feature animation in Japan. International releases under titles like “Panda and the Magic Serpent” extended anime’s reach before the TV era.

While storytelling choices reflect its era, the film’s color design and staging still read as a statement of intent. It was a clear signal that Japanese animation could mount large-scale features and compete for families’ attention at the theater, not just in shorts or educational reels.

Also Read

10 phrases that sound supportive but are actually a subtle sign of manipulation

#9 Momotaro: Umi no Shinpei (1945)

Momotaro: Umi no Shinpei (often translated as Momotaro: Sacred Sailors) is widely regarded as Japan’s first feature-length anime. Directed by Mitsuyo Seo during wartime, it expanded on earlier Momotaro shorts with a unified narrative and longer run time, marking a turning point in feature production.

The film was commissioned as propaganda, but its techniques showed how Japanese animators could handle sustained character animation, integrated music and continuity across sequences. Its legacy is technical as much as historical, illustrating the craft under constrained resources late in the war.

Later rediscovery and restoration efforts helped scholars understand pre- and mid-war animation practices. The feature’s survival offers a valuable record of layouts, timing and cinematography choices that would influence postwar studios.

It stands as a document of both art and context. While the message is tied to its time, the film’s execution charts a path from shorts to features in Japan.

Also Read

10 Phrases That Sound Supportive But Are Actually a Subtle Sign of Manipulation

That shift matters because it broadened what Japanese animation could be, giving later studios a reference point for full-length storytelling.

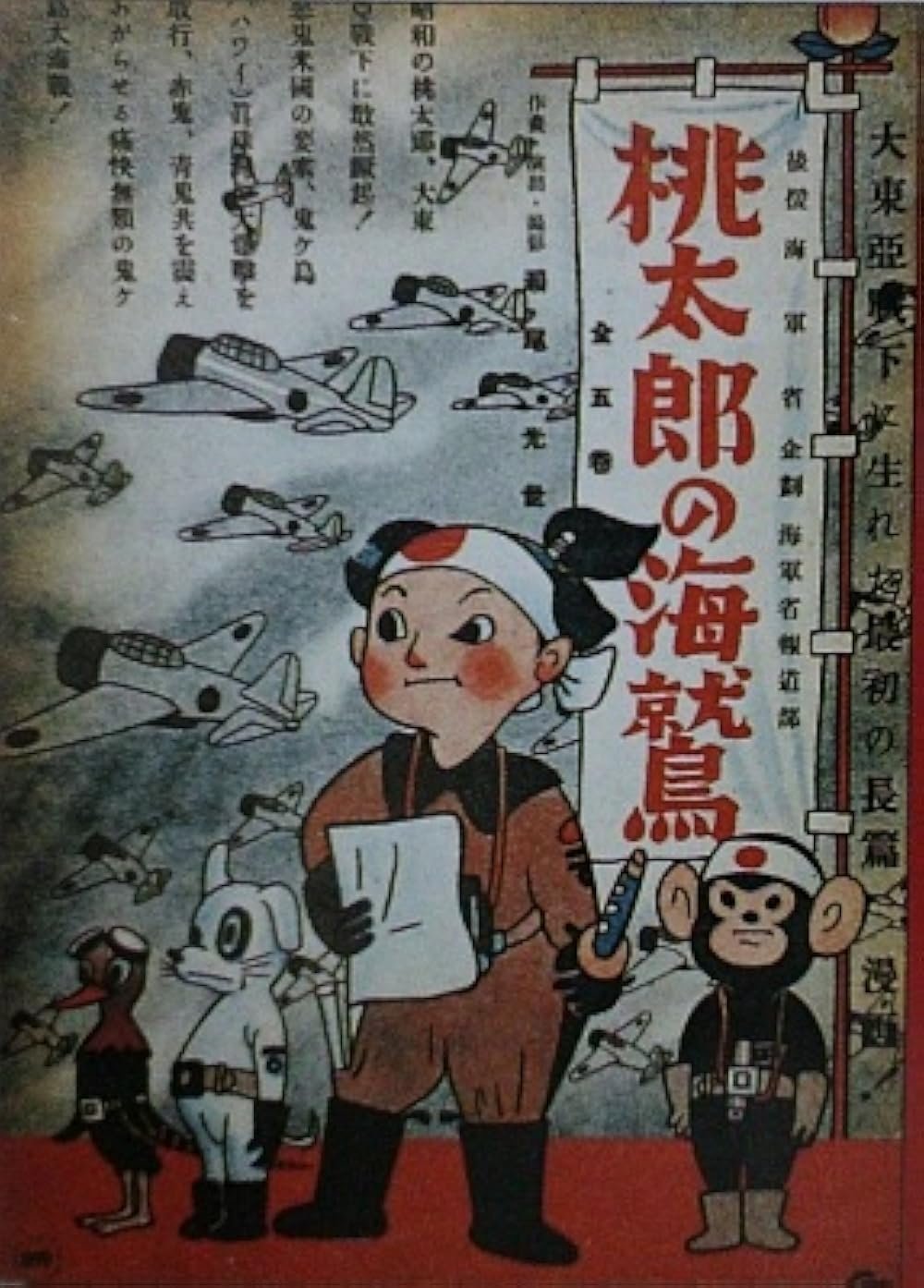

#8 Momotaro no Umiwashi (1943)

Mitsuyo Seo’s Momotaro no Umiwashi (Momotaro’s Sea Eagles) is an earlier wartime featurette centered on animal pilots. Though shorter than the 1945 feature, it demonstrated more advanced staging and synchronized sound than most domestic shorts of the era, previewing ambitions for longer-form narrative animation.

Its influence is visible in character groupings, musical motifs and montage sequences that later became staples in commercial anime. The project also shaped a production workforce that would carry skills into the postwar period, from timing charts to ink-and-paint practice.

As a precursor to the first feature-length anime, it is a key technical step. Even with its wartime framing, animators used the project to refine motion and cutting patterns that later TV directors and feature leads would borrow.

Also Read

People With Low Emotional Intelligence Often Miss These 6 Social Cues

#7 The Spider and the Tulip (1943)

Kenzo Masaoka’s The Spider and the Tulip is one of the best-known Japanese animated shorts of the 1940s. The simple chase between a spider and a ladybug showcases fluid motion, strong musical timing and atmosphere that felt refined for its length.

Masaoka’s team blended expressive posing with clean backgrounds and careful lighting cues. The short’s clarity made it a favorite in retrospectives and its craft demonstrated how effective animation can be with minimal dialogue. The film’s style later influenced children’s shorts and music-driven set pieces.

Its staying power comes from readable action and mood. With crisp staging and memorable character designs, it remains a touchstone for how to do a lot with very little.

For many historians, it also marks a maturation point. Prewar experimentation gave way to more polished work and this short sits near the top of that curve.

Also Read

8 Weird Habits You Don’t Realize You Have From Growing Up In A “We Can’t Afford It” Household

#6 Ari-chan (1941)

Mitsuyo Seo’s Ari-chan centers on ants and community, delivering clear character animation for the early 1940s. It is often cited for its staging and music integration at a time when resources were limited and techniques were still being defined.

What stands out is the rhythm of action. Scenes move with a steady beat and the character poses read cleanly even when the drawings are economical. That balance of clarity and economy became a recurring lesson for later TV animators.

The short also shows how animators communicated scale and teamwork with simple designs. Those methods show up again in postwar productions where constraints made concise visual ideas vital to storytelling.

#5 Imokawa Mukuzo Genkanban no Maki (1917)

Oten Shimokawa’s Imokawa Mukuzo Genkanban no Maki is often credited as the first Japanese animated film to receive a public release. The film itself is considered lost, but records describe a short comic episode starring the character Imokawa Mukuzo, adapted from newspaper cartoons.

Also Read

10 Phrases That Sound Supportive But Are Actually A Subtle Sign Of Manipulation

Even without a surviving print, the production marks a key milestone. It demonstrated that Japanese animation could reach theaters and it placed cartooning techniques into motion for local audiences. That theatrical presence helped seed demand for more shorts and encouraged further experiments by early pioneers.

The film’s reported methods included simple, direct posing and limited movement. That practical approach, born from time and budget limits, became a throughline in later styles of anime.

As a historical marker, it pushes the timeline back and confirms that organized production existed in Japan prior to other surviving prints.

It also frames 1917 as a breakout year, when multiple creators began exploring screen animation in a more regular, public-facing way.

Also Read

8 Cringey Phrases Older Relatives Use at Family Dinners That Younger Guests Dread

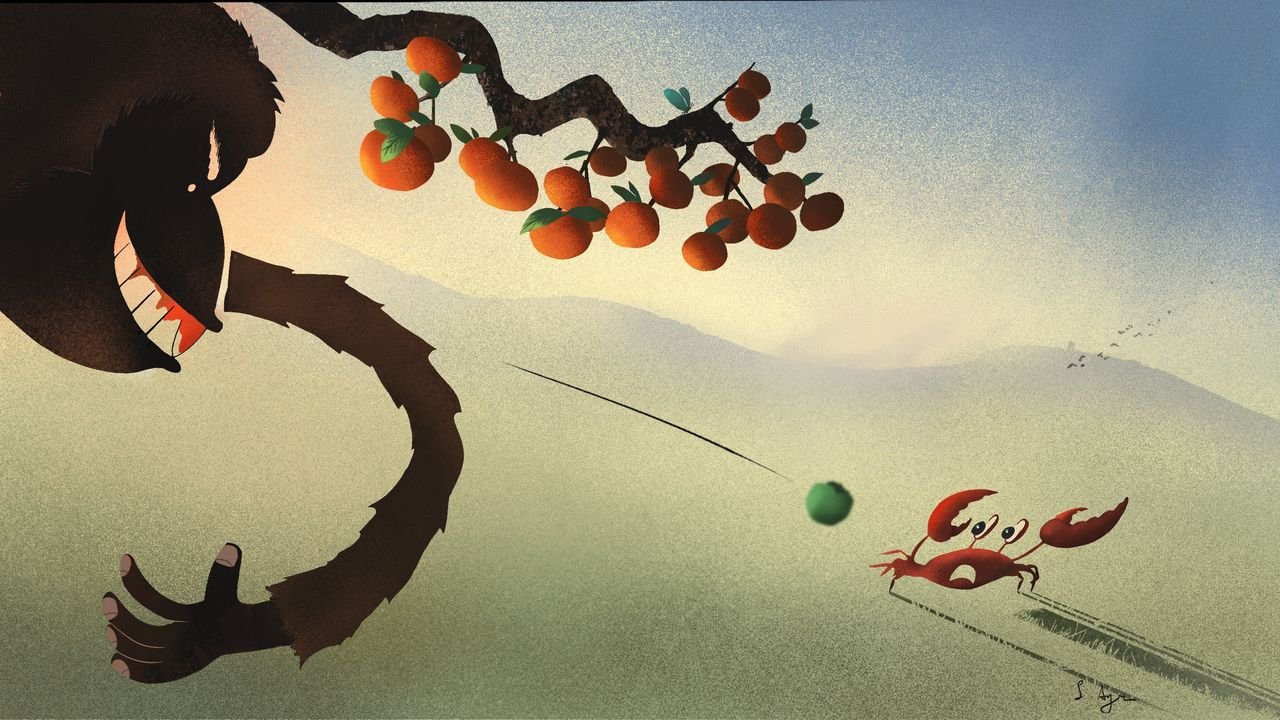

#4 Saru Kani Gassen (1927)

Yasuji Murata’s Saru Kani Gassen (The Monkey and the Crab) is among the most referenced silent-era Japanese shorts that still survive. It adapts a well-known folktale with clean staging and readable action, showing how the 1920s moved toward more consistent character animation.

Murata’s work highlights careful timing and simple geometric design. Those choices make motion easy to follow, a necessity in silent storytelling. The film reflects a maturing craft where animators relied on visual rhythm rather than dialogue.